Wouldn’t you love to be able to make a beautiful loaf of sourdough bread, but found the prospect too complex, confusing and time consuming? Wouldn’t it be also great if you could integrate it seamlessly into your already busy life? This blog describes a process for making sourdough bread that, if you follow it more or less correctly, will yield a rich, complex, nutty, flavourful sourdough each and every time.

This blog is the online accompaniment to my sourdough bread workshop I do for my food coop. Before going into the nitty gritty of the microbiological theory of sourdough, I’d like to start with a basic one loaf recipe. Even if you read no further, you will be on your way.

The basic loaf recipe – makes one 850g loaf

Ingredients

For the refresh

- 100g starter

- 100g water

- 60g flour

This will give you 260g of starter for your loaf.

For the rest of the recipe

- 150g starter (from above). Keep what is left for your next bread baking.

- 450g flour

- 240 g water

- 10g salt

Method

- Refresh your starter: combine 100g starter, 100g water and 60g flour in a 500ml jar. mix thoroughly, put a lid on it and leave it for between 6-12 hours at room temperature.

- Pour 150g into another jar or a bowl to use in your bread. Leave the remaining 100g in a jar in your fridge.

- Prepare your bulk rise: thoroughly mix together 150g starter, 450g flour, 240g water, 10g salt. Mix and knead until it is completely consistent.

- Place a damp towel over it in your mixing bowl and either leave it on the counter for 4-6 hours OR keep it in the fridge for between 12-36 hours.

- Prepare your proofed loaf: Your loaf will have risen.

- Remove it from the bowl and knead using the stretch and fold technique. Take a corner of the dough, pull it but not until it breaks, and fold it back into the middle. Repeat this process until the dough becomes stiffer.

- Prepare your banneton: place a dry cloth in the banneton, coating it with flour, or whatever grains and seeds you wish to be on the top of your loaf. This also helps the dough to not stick to the cloth. You can likewise use a loaf pan: instead of a dry cloth, line the pan with parchment paper and roll the dough gently in whatever toppings (if any) you want.

- Place your loaf in the banneton and generously sprinkle cornmeal on top as this will be the bottom of your loaf.

- Let it rest & rise either at room temperature for 1-2 hours, or in the fridge for up to 12 hours.

- Baking: Oven to 440F. Be sure your oven racks and pizza stone (if that is what you are using) are properly positioned so that when your bread rises, it will have some room.

- Prepare some parchment paper for the loaf to cook on. If you are using a baking tray, put the parchment paper on the tray. If you are using a pizza stone, put it on the counter and have a pizza peel ready to slide it into the oven. If you are making a pan loaf, line the pan with parchment paper.

- When the oven has reached 440F, turn the loaf out onto the parchment paper.

- Slash the loaf with a sharp knife. This is critical: a thin cut on the crust allows the bread to expand well in the oven (oven spring). See either Youtube or this Food 52 entry.

- If your bread has been at room temperature, bake for about 25 minutes. If it has come from the fridge, try 30 minutes. Each stove is different so you will need to experiment. Ideally your loaf should be at between 180-190F at the point it comes out of the oven. Use a digital thermometer. If you used a bread pan, it may take an hour.

- Let the bread rest for about 20-30 minutes before digging into it. It still continues to cook once out of the oven.

With this basic recipe hopefully successfully done, its now time to understand it better. The rest of the blog will help you to do this and provide tools to provide a wide range of options for your baking pleasure.

Understanding Sourdough

A basic sourdough loaf begins with 4 elements: starter, flour, water, and salt. That’s what you can see and measure. What you can’t see is the complex microbial community that also lives, grows and changes in it – until its baked, that is.

The wheat seed is pretty amazing little package containing everything needed to develop healthy growing micro organisms that have the potential to provide both nourishment, and future growth. There’s starches that provide the food, dormant yeasts, bacteria and enzymes too, that all work together to enable both sprouting and in our case, the development of a starter.

Lets begin with the yeasts: They are very simple little one celled organisms and don’t have a lot of needs. Their main need is food and temperature. In the case of sourdough, their food is sugar. Sugar is a pretty simple molecule, made from carbon, hydrogen and oxygen. However,it is not available in any great quantity in the wheat seed. Starches are available, and these are quite complex molecules – imagine a long train of simple sugar molecules. They need to be broken down. Fortunately, there are also enzymes called amylaces. When they are combined with water, they are activated and go to work to break down the starches into simple sugars. Once the starches are converted to simple sugars, the yeasts in the flour can now get to work and consume, reproduce, and off-gas carbon dioxide.

The starter starts off as flour and water, but growing in it are important living lactic acid bacteria – Lactobacillus. This is the same bacteria that lives in your digestive system, fights pathogens and generally keeps you healthy. Its what is in probiotics, yogurt, and all fermented foods. They are in the flour as well, and like the enzymes and yeast, need water to activate them. The lactobacillus also metabolizes sugar to provide that distinct nutty/tangy flavor.

The yeasts and bacteria grow best at different temperatures. Sourdough yeasts can grow and develop in a in a wide range of temperatures from 10C to 35C. Their optimum range is between 25-30C. When they are baked, they die off after about 45C degrees. The variety of lactobacillus bacteria present tend to prefer higher temperatures. Most people prefer room temperature as this often provides a good time window for the rising. It also gives the bacteria more time to develop, and thus a more complex, nutty flavour.

Yeast reproduce by budding. A small node develops on the yeast cell, becomes bigger until it finally separates, leaving 2 cells. In the picture below (left) you can see the two yeast cells on the left budding, the one at the bottom has just separated. The picture on the right shows lactobacillus bacteria in their colony.

Here’s a video of yeast reproducing.

We can use this information to effectively control our sourdough times, and taste. For example if we want to have a faster rise it can go on top of the fridge, or in a slightly warmed oven. If we want it to take longer, – if we want our bread to rise while we’re away at work for about 9 -12 hours might be an idea to put it in the coolest spot in the basement, or the fridge.

The taste can be manipulated too: The more lactic acid bacteria (LAB) there is, the tangier it is. LABs tend to develop more slowly than yeast. Thus, leaving it longer will encourage the lactobaccili bacteria and give a tangier loaf.

The starter

The starter is the most important key to great sourdough. Its the home to numerous micro organisms including the yeast. Its responsible for both the rising and the taste. Through its care, you can manipulate it to achieve different results.

mixing the starter refresh

Every starter is going to naturally mutate with time, and acquire its own special characteristics. Initially its important to see how long your refreshed starter takes to fully bloom. Put a piece of vertical tape on your jar and note the time and temperature of its rise. This will give you vital information about your starter characteristics. In my case, its 8 hours at 22C. What that means is that when I put a new loaf together, AND decide to do it all at room temperature, it needs to do its bulk rise and proofing all well within that 8 hour window. This will assure me of a successful loaf with great oven spring. It also means that I can likely retard the rising to 9-12 hours by keeping the bulk rise conditions at a lower temperature – say 10-15C. On the other hand, the rise will be a lot faster on a humid day in summer.

Taking care of your starter

Keep your starter in the fridge – especially if you want sourdough to be reliable and easy to maintain. At this temperature, it remains not quite dormant yet ready for use. If you keep your starter at room temperature it’s going to be very active until it starts dying off and you will be spending a lot of energy refreshing it. It can remain viable in your fridge for over a month. With time, you will develop your own way to best manage your starter.

I like to keep approximately 300g of starter between bakes. I refresh this with 300g of water and 180g flour. (780g total). I’ll use 400g of starter to make a bulk rise for approximately 3 loaves. To see how this method works, see my Making Sourdough Easy and just in time blog.

The whole rising cycle

This great diagram (below) from http://www.classofoods.com/page1_3.html shows the evolution of the yeast and bacteria in the bread. (You may need to click on the image to see it clearly.)

The lag phase is seen initially in the bulk rise: you look at it and nothing appears to have happened. There is however a lot happening: Water has activated the enzymes in the flour that convert the starches in the flour to sugars.

In the exponential growth phase it expands. The yeast is now actively eating the sugar, reproducing, and emitting carbon dioxide. It should be proofed and baked in this period.

When it reaches its stationary phase or beyond, the sugar has been metabolized and the yeast cells are going dormant.

What does this mean?

- When you refresh, you want to have the maximum amount of yeast cells available so its best to let the refresh period run until the plateau phase when there will be the maximum number of vigorous yeast cells.

- When you bake, the bread needs to be in the oven well before it has completed its exponential growth phase. This enables the final part of the exponential growth phase to occur in the oven.

- Every time you add flour and water to a starter or even an existing dough you are beginning this yeast cycle all over.

Baker’s percentage and Hydration

There are two very important terms to know about in bread making: Baker’s percentage and Hydration.

Baker’s percentage: Usually percentages add up to 100 – except for bread. The weight of the flour you use is always 100%. All of the other ingredients are expressed as a percent of the weight of the flour. Thus if you have a loaf that has 1000 grams of flour and you add 20 grams of salt, the baker’s % would be 2%. Every single ingredient in your bread can be expressed as a Baker’s Percentage. If this 1000g loaf had 20g salt, 600g water, and 50g starter, the Baker’s Percent for the whole loaf would be 167% (100+60+2+5).

Hydration hydration is the wetness of the dough, the ratio of the flour to the water expressed as a percentage. It’s the weight of the water divided by the weight of the flour. If you’ve got a 1000g loaf (100%) and you add 600 grams of water (600/1000) = 60% hydration. In the starter, 250g water/150g flour gives a 166% hydration.

Final bread hydration is usually anywhere between 60% to 85%. 85% gives you a very wet dough, but one in which the yeasts will appreciate the extra water medium. Even 1% makes difference in hydration. My personal go-to ideal hydration for an everyday pan loaf is 66%, or 66g of liquid for each 100g of flour.

The key to moving on from the fixed set of weights and ingredients to scaling up or down your production, or creating different kinds of breads will be facilitated by using this hydration table.

This hydration table/worksheet has a variety of tabs along the bottom that correspond to the type of baked good you want to make. Its simple to use: you can only change the yellow cells. Changing these will change the formulas telling you how much flour, water and salt to add. All the other cells are locked, so you can’t destroy it accidentally. Until you get used to it, I suggest changing only the amount of starter, as this will scale your recipe up or down. After you are more used to it, you can play with the hydration and ratio of starter to flour.

In addition to the basic dough, there is a sheet for sourdough pancakes and sourdough crackers. Each of these 1st 3 sheets is formatted to work well on a cell phone display.

If this is a tool you find useful, you will probably want to download it as an Excel file, or make your own google sheet copy. Downloading to Excel will remove all the cell protection.

Equipment

Beyond some basic kitchen gear such as mixing bowls, spoons, jars, oven mitts and of course a stove, here’s the other gear you need.

Must have’s

- A scale: good electronic scales are widely available at hardware and kitchen stores. Make sure it can take up to 5kg. Once you start using it you will come to appreciate the consistency it gives you in your cooking.

- A good bread pan: thick, no rust. Have at least one that is the size of a pan loaf you want to make.

- 1L glass jar – preferably wide mouth. This is for the starter beast in your fridge.

- Pastry brush: to oil the pan, spread toppings or egg white before baking

- Electronic kitchen thermometer: Until you get completely used to your oven/bread/timings, you need to be sure the baked bread is at least at 190F/88C when it comes out of the oven.

- Parchment paper: use it to line baking pans, to put under pitas, pizza, batards, boules or baguettes. It makes their transfer in and out of the oven really easy. It also saves you on the cleanup.

- If you are making boule or batard styles, you should invest in bannetons, a pizza peel, and a pizza stone, though a cooking tray can work in place of a pizza stone and peel.

Good to have

- Pizza stone: It means that the bottom of your pita/pizza/boule/batard hits a very hot surface when it goes in the oven ensuring more even cooking and a great crust on the bottom. The pizza stone must go in before you turn the oven on.

- Pizza peel: to move things on and off the pizza stone easily

- Bread scraper: to help with stretch and fold, clean your surface, help your bread out of the pan

- Water spritzer: Spritzing the loaf after its been in the oven a few minutes helps the crust get nice and crunchy.

Optional

- Baguette couches to rise and bake baguettes

- Other bake pan sizes

- rising bins: These are large plastic bins many pro bakers use for bulk rising a lot of dough.

- a lame – an old fashioned razor blade to slash the bread. Sharp knives, especially serrated knives, work well too.

Other foodstuff to consider:

While you can make a very simple bread with only flour, salt, water and starter, you inevitably will want to consider other additions:

- oil to brush on the pans

- egg white to brush on top

- wheat germ, any kind of grain, small seed, sunflower seeds either mixed into the dough during your stretch and fold or as part of the crust

- herbs/spices/garlic/cheese (as in making a herbed foccacia for dinner)

Doing it!

This section goes into the recipe in some more detail than the straight-up recipe at the beginning of this article.

Refresh

- Refresh the starter you need for your loaves: the amounts of water flour and original starter are built into the hydration table. Do this 6-8 hours ahead of mixing. This will assure you of a well refreshed starter. Always make more starter than needed for your loaf – for your next bake.

- Plan out what bread(s) you want to make using the hydration table. The same dough can be used to make several different products.

- If your starter is highly active and you want more of a sourdough tang, use more starter – as little as a 3:1 ratio to the flour. If it is a little older, you may want to use less – up to 20:1. Doing this will delay the proofing time.

The Bulk Rise

- Thoroughly combine and mix flour, water and starter together.

- Wait 20 minutes. This wait period is called the autolyse (when the enzymes are converting starches to sugar). The flour is hydrated, fermentation begins, the proteins stretch out, the gluten has a chance to begin its development in the absence of salt.

- Add in the salt: 2% of the weight of the flour. The salt is critical to toughen up the dough and slow down the fermentation.

- Knead until well combined, put in a bowl with a wet cloth, noting the temperature you are rising it in.

The beginning of the bulk rise

- Let it rise: Place a damp towel over it in your mixing bowl and either leave it on the counter for 4-6 hours OR keep it in the fridge for between 12-36 hours.Initially you’ll need to explore parts of your own environment to identify the micro temperature variations that will be right for you. When you gently press it it should indent, not collapse, and slowly spring back. You can stretch and fold the dough once or twice in this period. This removes gasses from the dough, allows the yeasts and bacteria to become acquainted with other parts of the colony (and maybe more food) and helps the dough rise evenly. This process is optional.

- Ideally it should be in the middle of its ‘exponential growth’ phase. The dough cannot have finished its full rising at this point, otherwise it will be overproofed by the time it hits the oven.

Shaping the dough and proofing

- Remove it from the bowl and knead using the stretch and fold technique.

stretch one corner of the dough…

and fold back to centre….If your dough has been refrigerated, it will not stretch and fold easily. In this case, just knead it out. The result will be the same: you are working to knock the CO2 out of the dough, and strengthen the gluten.

- Let it rest while you prepare your pan(s) (assuming you are making a couple or more bread products).

- If you are making more than one loaf, divide it into however many loaves/pitas/buns etc. then begin a second stretch and fold with each one that culminates in them being in their final shape. Use your scale: loaves and boules are typically 800-1000g, baguettes: 400g, buns and pitas: 100g or so.

- Shape your final loaves. Youtube is a great resource for observing specific techniques for specific kinds of breads: Loaf pan, boules and batards, baguettes

- You more than likely will want to include crust toppings. Here are some ideas:

- Brush on oil if you are using a pan.

- A variety of grains, nuts, and seeds always go well. They also form an important layer between the bread and the pan to prevent it all sticking.

- Adding garlic, herbs and cheese into a baguette gives an excellent dinner side

- Corn flour or regular flour as a dusting on the top or bottom works well

- White egg wash will glisten up the top

- Oil or melted butter brushed on the top browns it nicely too.

sesame buns on parchment paper

- Slashing is critical: a thin cut on the crust allows the bread to expand well in the oven (oven spring). See either Youtube or this Food 52 entry.

- Use parchment paper for anything going on a pizza stone. It makes it so much easier!

- Once you have prepared your loaf, you have two options:

- put your loaf in the fridge, and put it directly into the oven from the fridge

- Let the bread(s) proof for about an hour, until it has begun to rise and will slowly spring back after being gently poked.

Baking

Bake your loaves using these general guidelines. Finished bread should be between 190 and 205 F. Typical bake times:

- A batard or boule in a banneton @ 800g: 440F/225C for 26-30 minutes

- for an 800g loaf – 450F/232C for 12 minutes, 425F/218C for 12 minutes, 400F/204C for 12 minutes

- For a pan loaf cooked directly from the fridge: 450 for 15 minutes, 425 for 14 minutes, 400 for 13 minutes.

- Pitas take about 3-4 minutes at 450F/232C, preferably on a baking stone

- Baguettes and buns take between 12-20 minutes at 450F/232C: the bigger the loaf, the more the time.

- Due to the fact that your oven drops 30 degrees every time you open the door, I prefer to cook my different kinds of loaves separately, though I sometimes will throw in a baguette when a pan loaf is 1/3 cooked.

Disclaimer: This works for my oven which won’t necessarily be true for yours. Your final loaf should be between 190F-205F when finished.

When the bread is baked, remove from the oven and their pans. Check the internal temperature. It should be between 180-190F as soon as it comes out of the oven. Allow them to cool for at least 30 minutes.

Fitting sourdough into your busy life

Integrating sourdough into a busy working life is perhaps the biggest barrier to starting it in the first place. Initially it might seem too complex, concern about timing not fitting in well with your wake/sleep/go to work schedule. I’d argue that this can be easily worked around. Your biggest asset to making it succeed is your fridge. Because your fridge severely slows down fermentation, it gives you a lot of latitude in planning your breads.

For example, you could as follows:

- Refresh your starter after you finish cleaning up your kitchen after dinner.

- The next morning you put a bulk rise together before heading off to work, and slide it into the fridge.

- When you get home, and are preparing dinner, the first thing you do is to take out the bulk rise, shape it into a loaf, and let it proof in the warmest part of your kitchen for an hour or longer if possible.

- About 45 minutes before dinner is ready, make sure the oven is near 440F and your oven racks/pizza stone are in place for the bread. It may mean you need to sort out other oven usage. Even if you have something already in there at 400F, your bread will still bake – it will just take longer.

- Bread goes in 25-30 minutes (at 440F) and is ready to eat 10 minutes after coming out.

Bulk rise for all occasions

Its also a good idea to anticipate how much bread your family is likely to eat on an ongoing basis. Using the hydration calculator, develop proportions that will provide enough refrigerated bulk rise dough for about 4 days. This means you can always have a base dough in the fridge. It can be used to make bread, pizza, pita, baguettes – whatever is required. You can decide what kind of loaf you want with a 2 hour time frame.

My suggestion is to also have a loaf prepared to go into the oven already in the fridge. This way, whenever you decide you need a loaf, turn on the oven, and pull it out. The dough does not have to be at room temperature before it goes in the oven.

- When beginning it, do your initial tries when you are not going to work. Use the hydration table log to record your changes and observations, and to get a feel for it.

- Identify some of the following:

- What time of day do you want it to appear out of the oven? (set this as your goal)

- When are you not around in your house?

- When is your usual sleep/wake cycle?

- Keep in mind:

- Initial mixing takes about 15 minutes over a half hour period.

- You do not have to be around for the bulk rise

- The final proofing will take between 1-3 hours from beginning to the end of baking, of which you will be actively attending to the bread for between 10-30 minutes depending on how much you are baking.

- Consider baking directly from the fridge. In this case the loaf has proofed for 12-24 hours in the fridge and goes directly into the oven. This will cut down on your ‘need to be around while the bread proofs’ time. If you bake it directly from the fridge, plan one hour from “I’m going to turn on the oven” to “OMG this is delicious!”

- Think creatively of various places in your house that are either warmer or cooler, ranging from a warmed oven (heat to its lowest temperature, then turn it off) to your fridge. Even within your fridge there will be cooler and warmer areas. Basement floors can be really useful if you are in a house.

- If you completely blow it and either under or overproof it, and you know it, pitas or pizzas are incredibly forgiving, and you will still be more than appreciated for the result.

- Make a plan that takes into account the needs of the bread and your own time needs and commitments. Try it out, reflect – talk about it with other bakers either near you or on the forums noted below – you will find a solution!

Resources

I’d like to point out some really important resources: This blog and the workshop I am giving are but door openings into the magical wonderful world of sourdough. There is so much more to know, and to experiment with.

- The Fresh Loaf is a really thorough and comprehensive site with its own very interactive discussion forum wrapped into it.

- Northwest sourdough is the work of Theresa Greenaway, a West Coast sourdough expert baker and teacher. The work I am presenting to you is directly derivative of her work. In her 4 volumes on sourdough she authoritatively covers all the possible uses from breads to quickbreads and cakes. I would strongly recommend getting all four of her books.

- Related to this is the https://www.facebook.com/groups/perfectsourdough/ which has a faithful following of both expert and newbie bakers.

- And another facebook sourdough group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/360136781918/

- Wild Yeast is another baking blog focused on sourdough

- The Tartine Loaf is legend on the west coast and this you tube shows you how. This loaf was the focus of Michael Pollen’s AIR chapter in Cooked, also an excellent read.

- Bread science is expertly covered by Emily Beuhler in her book of the same name.

- Check out the Lactic Acid in Sourdough article for a technical but easy to read explanation of the chemistry of it all.

- The Clever Carrot is a blog of similar scope to this one – well described.

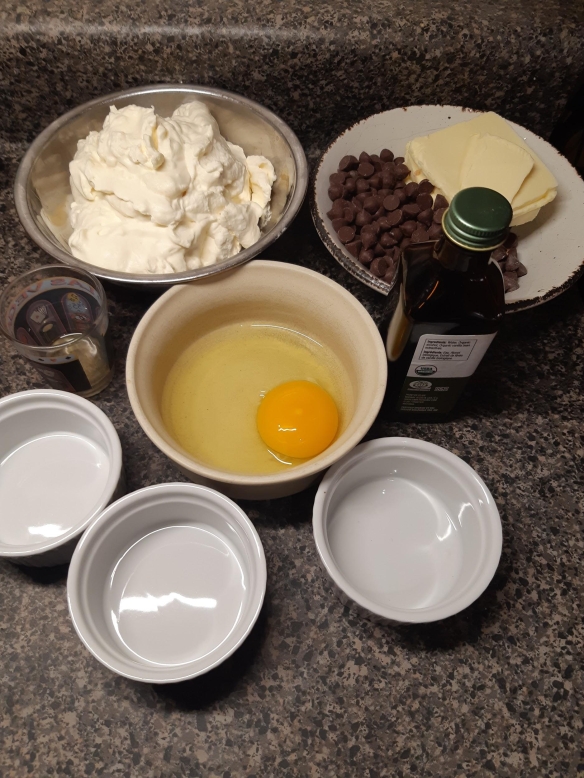

Here is the resulting mise en scene for a double batch:

Here is the resulting mise en scene for a double batch: